One thing you can say for Oppenheimer: watching it is a clarifying experience.

In Oppenheimer, the Trinity Test is presented as a fixed point in time. Christopher Nolan treats it almost as a mythical event: every other part of Oppenheimer’s life either leads up to that moment, or is fallout from it. It is the crux of the film, around which all other action revolves and radiates. In a way, the movie gives all of us living on Earth such a point when it shows us Trinity.

“Oh, this is what will kill us all,” we can think, with a weird kind of relief.

It’s out of our hands.

But of course that isn’t true. The thing that will actually kill us all, and is, as I type, is the tiny natural shocks of war all over the earth, right now, that we could stop. It’s famine and drought and terrible cold. It’s what we’ve done to the climate, collapsing out from under us while we fetishize billionaires who want to move to uninhabitable planets without us.

When Oppenheimer imagines the atmosphere set alight, blooms of fire bursting up across the entire globe—well, we’ve done it. It’s happening now. Air is unbreathable, uncontrollable wildfires chase summer around the globe, species drop like flies, bees drop like the rain that we can no longer drink.

Is it easier for me to latch onto Oppenheimer than to think about how the seasons have shifted in the two decades of my life in New York? About how my dad lives on a waterfront property in Florida, about how November will be here before I know it, about how I never saw geese migrating last fall, about how there was a cherry tree in full flower across the street from my friend’s apartment, in Brooklyn, in December.

This is going to be a long and winding essay, even for me. These are ideas I’ve been batting at and knocking off countertops for months now. I tried to stop myself from needing to Have A Take, or to beat anyone else to the punchline. I’m just going to think on paper… or I guess screen.

A few months ago, I noticed a trend in films that were trying to speak about unspeakable things, and I was caught by some odd commonalities among films I didn’t expect to be in conversation. What did they have in common? Why were they all knocking into each other in my mind like pool balls after a break? I’ll primarily be looking at films from the second half of 2023, namely: Asteroid City, Killers of the Flower Moon, Godzilla Minus One, and, as I’ve already started with, my beloved Oppenheimer, which currently stands as the film I have seen the most times in the theater. (Four times, it would be five if not for an ice storm. And I’m watching it again at a friend’s the day after tomorrow.)

The more surprising film is 2019’s A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, a lightly fictionalized account of a friendship between Fred Rogers and journalist Tom Junod. (This might make sense once I get there.) David Foster Wallace is also in here a little, as is Conan O’Brien, but first let’s talk about metamodernism—a theoretical school I only barely understand.

When I first thought about these films it was in a conversation with metamodernism, a loosely defined theoretical idea that is a reaction to both modernism and post-modernism. I’ll be honest, I’m still not sure if there’s any there there—compels me, though. The best way I’ve found to think of it is in terms of late-night talk show hosts: Johnny Carson was a sincere, urbane, deadpan Modernist; David Letterman, the cynical post-modernist reaction against Carson. One created an aspirational television reality of urbane wit and glamorous women that the majority of the country tuned into every night; the other took that reality and poked snarky holes through it, mocking the idea that you could take the show or its guests all that seriously. How to react to the reaction? That’s how you get Conan O’Brien, who combines sincerity and absurdity, and succeeds, I think, because after forty years of being basted in cynicism—but with full-frontal sincerity a long-lost glimmer in the cultural rearview mirror—a lot of younger people experience culture in an oscillation between irony and sincerity that is so rapid it creates a secret, third emotion. Conan harnessed that oscillation in the service of establishing a joke that the guests and audience are in on together. He spent the latter part of his career literally traveling the globe to meet people, and now invites fans onto his podcast to speak to him, as well as the expected celebrities. (I should also note that it feels more natural for my fingers to type “Conan” than his full name, which speaks to something.) Conan, if my example holds, embodies a metamodern aesthetic.

I’m mentioning this because he uses artificiality to get at actual connection—compare this with, say, the MCU’s approach to humor, where almost every moment of real gravity is undercut with a snarky aside, and almost every death and consequence is undone via multiverse shenanigans or plot armor. Compare it with most of the really popular current comedy, where all the characters are sarcastic quip machines or life itself is so cringe that the audience members’ skin crawls off their bones to go watch Columbo in another room.

Or maybe a better example, given that I’m going to talk about movies from here on out, would be Everything Everywhere All At Once, which is a wacky surrealist comedy, a commentary on diaspora culture, a tearjerking story of a mother learning to accept her queer daughter, and a realistic look at two middle-aged people in a difficult marriage figuring out how to love each other. The film is extremely polarizing because it attempts to squash so much into its runtime, and, I think, because it commits to all of its elements (all at once), and comments on all of those elements, at the exact same moment that it’s hoping its audience is finding a genuine emotional experience in it. From what I’ve seen among my friends, film reviewers, and in my own internet bubble, a lot of people seem to like it because it captures a sense of How It Feels To Be Alive Right Now. But this is also deeply off-putting to a lot of people who feel like it overreaches.

I found myself circling the idea of metamodernism as I wrote because of a quote Cillian Murphy gave when people asked about his performance in Oppenheimer. He said that a key to his performance came when Christopher Nolan described Oppenheimer as “dancing between the raindrops”. Patterns of raindrops in the film make an easy mirror to Oppy’s visions of quantum reality, and to the reaction caused by nuclear fission, but they also mirror his attempts to balance all of his own contradictions. This was what I loved in the performance, this constant, many-layered high wire act of performing intellectualism in a way people could understand, actually being a genius underneath that, using deadpan wit as a defense against military brass, as a flirting technique (“I read it in the original German”), and as a release valve with other scientists, being entranced by the beauty of the bomb, being triumphant that it works, but also being horrified beyond the capacity for thought by what he’s done. If we find this term useful, we could call this is a metamodern performance—especially because it creates a blank, shining chalkboard for all of us to write our own opinions across Cillian Murphy’s tormented face, and see if there’s any there there.

But the more I wrote about it (and I wrote a few thousand words in an earlier version of this essay) the more it felt, not wrong, but like I wasn’t getting at the heart of the conversation. I wanted to find a simpler way. One that doesn’t require me to sum up 60 years of late-night television in three sentences.

And then I found the key, or I should say two keys, in a very unlikely place: 2019’s A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, a film inspired by “Can You Say…Hero?”, an Esquire profile by Tom Junod.

In the profile, Junod meets with Mister Rogers, they speak a few times, and Junod accompanies Mister Rogers to the gym, and to a few events in New York City. The interview is intercut with descriptions of Mister Rogers’ day, people’s reactions to him, some of his personal history, and some of Junod’s own emotional musings. There are moments of startling vulnerability—not from Mister Rogers, from whom we expect that, but from Tom Junod, who seemed to want to open himself up to Mister Rogers’ way of looking at life.

The profile fits a recognizable shape, and it’s good, but where this becomes interesting and relevant to this essay is that the film adaptation does not do that.

The film adapts several of the scenes from the profile to fit its plot—Tom Junod is transformed into the fictional Lloyd Vogel (played beautifully by Matthew Rhys, his dial turned to MAXIMUM SAD) a cynical, somewhat troubled journalist; a conversation with a child in Penn Station is transposed to the Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood set; a request made to a child in real life is instead made to Lloyd Vogel’s estranged father, who’s played by Chris Cooper.

But one of the reasons it hit me harder on rewatch, and brought the other films into focus, was the way it chose to take the magazine profile and play with the boundaries of fact, fiction, image, irony, sincerity.

The movie in a lot of ways becomes an episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood for adults. It’s takes a couple of thorny issues—new parenthood, the deaths of parents, a cynical worldview that’s short-circuiting any capacity for joy—and translates them into “this makes me mad” / “this makes me sad” but again, for adults. There are moments when we watch episodes of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood being filmed, and moments when Tom-Hanks-as-Mister-Rogers is speaking to the (presumably adult) audience watching the movie the same way the real Mister Rogers spoke to the kids watching his show. Most of the exteriors in the film are actually miniature sets a la The Land of Make Believe, with the camera panning between a miniature downtown Pittsburgh to a miniature downtown New York City to move us from Fred Rogers in his studio to Lloyd Vogel and his wife and baby in their apartment, or to the Esquire offices. Mister Rogers shows the audience how an issue of Esquire is put together via a 1980s-style filmstrip on Picture Picture. Some of the most heartfelt conversations involve puppets. Raw human emotion happens in a television studio, refracted through the recording eyes of cameras and TV monitors. The lines between “real life” (Tom Junod, Fred Rogers, and the conversations they had in 1998), scripted conversations (between Rhys as Lloyd Vogel and Hanks as Mister Rogers), and performance (Tom Hanks as Mister Rogers performing in an episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood), are blurred and trampled and remixed all the way up to the end credits, where we’re shown behind-the-scenes footage of the craftspeople making the Pittsburgh and New York City miniatures.

While it’s not a perfect movie, the parts that work are extraordinary (and, weirdly, do a lot of what I wanted Barbie to do?). I’ll admit that I, a person who does not cry, might have maybe teared up a bit, although we must take into account that the movie takes place in my old hometown, Pittsburgh, and my current-and-hopefully-forever hometown, New York City, and then there’s the Nick Drake song to contend with.

All of this artifice is created with the practical effects of miniatures and sets. By calling attention to its own artifice, and allowing jaded adult viewers to think they’re in on a joke of some kind, it leaves us vulnerable to a couple of moments of shocking sincerity. I’ll get into them in more detail a bit further down, but I needed to talk about this first to get to one of the actual things I want to talk about, which is the mediation of catastrophe.

My beat, such as it is, is pop culture. When catastrophes happen, or should I say when humans choose to inflict horror on other humans, what I end up doing is trying to find a way to talk about it through pop culture. To try to make sense of us through the art we create, the movies we shower with Oscars, the TV shows we tune into every night.

I’m always looking for a new way to describe reality, and that’s what I’m going to try to do now.

I saw a few reviews that said some variation on “with Asteroid City, Wes Anderson has gone existential” but I think he and existentialism have gotten to third base plenty of times before now. His films all deal with grief in various ways—people seek vengeance, they wear their dad’s glasses, they become obsessed with creating a found family, confronting an estranged relative, excelling in school. I’m guessing most people have done at least one of these things out of grief, just to try to make sense of it. And again, Anderson always has these (forgive me) monoliths (that get a little more monolithic with each movie) looming over the characters either as rebukes or mountains to climb: Rushmore Academy, The Tenenbaum’s House/The Impossibility Of “Going Home”, The Sea Itself, India/Some Sort Of Ill-Defined Holy Plane Of Existence, Moonrise Kingdom Itself, The Grand Budapest Hotel Itself/Europe/The 20th Century As A Concept.

But Anderson’s latest two (feature-length) films are explicitly about the creation of art—specifically whether the creation of art can help with grief or foster connection. And they both fold in on themselves endlessly, endlessly, bringing in authors and theater directors and editors and grammarians and journalists and actors, all to point out that the characters they’ve constructed are, in fact, characters they’ve constructed.

The trick is to get you to feel something anyway. The trick, as ever, is in not minding that it hurts.

While The French Dispatch (my current #1 Anderson) does this through longform magazine profiles, painting, manifestos, comics, and flashback-riddled television interviews, Asteroid City does it with a play-within-a-documentary-about-said-play that never met a fourth wall it couldn’t break.

“Asteroid City” is a fictional play that’s being discussed on a Playhouse 90-type show, with a Rod Serling-ish host, in the 1950s—back when people were still figuring out what TV was and you could get away with something like that. But hang on, there are layers:

The Host is the host of the show, but is also telling us, the modern movie audience, about the broadcast of the play, which was written solely for this fake documentary. Though he’s in glossy sci-fi black and white, he seems to be looking back at a time long past. He stands downstage and talks directly into the camera as he tells us about the writing and production of the play.

The play vignettes begin on stylized sets: playwright Conrad Earp’s office/library, theater director Schubert Green’s stage, and the backstage area he’s turned into a makeshift living space, the rehearsal space of Saltzburg Keitel’s Actor’s Studio-esque workshop. As we’re dropped into each scene the camera pushes in until, it seems, we’re watching real people fight, seduce each other, and workshop, all in service of a real play. But of course we’re not, we’re watching a dramatization of The Host’s reminiscences about the creation of the play “Asteroid City”.

When we’re dropped into “Asteroid City” itself, it isn’t in black and white, or being filmed on realistically grainy 1950s film stock—it’s glorious widescreen full-color Hollywood Old West, beautiful bright matte paintings and model trains. And as we meet the characters, whom we know are all being played by actors, some of whom we met in the black and white sections, it turns out that they, too, are playing roles. Midge Campbell is a Marilyn Monroe-style bombshell who’s preparing for a role while her daughter attends the Junior Stargazers camp. She runs lines with Steenbeck, paints bruises on her face to get in character, and talks about how she’ll probably end up dead of a barbiturate overdose. Practically, this means that Scarlett Johannson plays Mercedes Ford, a serious stage actress who’s playing Midge, who, in the world of the play, is herself prepping to play her latest in a line of abused and suicidal film characters. Midge talks about being a skilled comic actress, which is both a switcheroo reference to Monroe, who was typecast a dizzy blonde when even though she was a remarkably good actress who studied with the Actos Lab and Paula Strasberg, and a riff on Johansson’s own career, where her comic timing has been forgotten amidst MCU action and high concept sci-fi.

“Asteroid City” the play is about grief and the inability to connect with objective transcendence. Asteroid City the movie is about mediation, its failings, and observation all the way down. The desperation to be seen. Not just the obvious—the Observatory, and the Observation Deck overlooking the asteroid, but also Clifford Kellogg constantly saying, “Dare me?” and then hoping the others watch him attempt feats like jumping off roofs and climbing cacti. It’s in the two times a youth group member is asked to pray, and the prayer is simply a recitation of everything that happened, in case God missed any of it. The youth group members’ parents watch them on a closed-circuit TV. Both Steenbeck and Midge Campbell enact grief for each other, hoping, literally for a grief observed, even while they don’t want that AT ALL.

And of course when an Alien comes down, the one fully outside observer, it says nothing, gives no indication that it cares about the humans in any way—it’s just stopping by to borrow the asteroid.

When we see the director, Schubert Green, that’s part of the documentary. We see Jeff Goldblum playing an unnamed actor in costume as The Alien. We see the “spaceship”, a pie plate painted green. But we also see Jason Schwarztman as Jones Hall playing Augie Steenbeck step off the stage, walk backstage, and step out onto a balcony for a smoke, where he ends up speaking to Margot Robbie as the unnamed actress who played Steenbeck’s wife, who has coincidentally just stepped out onto the balcony of the theater across the alley. Two Juliets face-to-face. She was the actress who played his wife in a dream sequence in “Asteroid City”, before it was cut for time. (Or as he says: “You’re the wife who played my actress”.) They play the scene, balcony to balcony, just as he and Scarlett Johansson as Mercedes Ford as Midge Campbell have been rehearsing the scenes for Midge’s upcoming movie.

The cut scene was a dream sequence, set on the Alien’s planet. Within the play, it was a chance for Steenbeck to voice some of his fears about living without his wife. You can see it, with a little imagination, and you can more or less guess where it would have fit into “Asteroid City”, the play, and how it would have impacted Asteroid City, the movie, and how it would have brought Steenbeck’s anxieties to the surface of the play-within-the-movie—and given the movie an emotional payoff that Anderson denies us. It also would have returned us to the Alien. Even if only through the mediation of Steenbeck’s dreaming mind, we could have had a bit more meditation on its meaning and symbolism. Instead we get it as a bare bones dialogue between Jones and the unnamed actress, in the last few minutes of the film, staged as a stolen moment between two actors, one of whom isn’t even in the play anymore, and it’s being played to no audience at all. It’s just for the two of them.

Except, of course, that it’s being played for the audience of the documentary. It’s showing us what we’re not getting.

But, too: not giving us that dream sequence leaves the Alien as it is, an unknowable mystery, an uncanny moment burrowed into the heart of the play and the movie, inexplicable, captured in Steenbeck’s photograph, sure, but no closer to being known.

Where does mediation get us, in the end? But what else do we have?

The Godzilla mythos is, at its heart, the mediation of catastrophe. What was done to Hiroshima and Nagasaki is too large and horrific to think about. Only the people who experienced it will ever really understand it; pictures, documentary films, writings—none of it will get there, I don’t think. What I find amazing is that, faced with this reality, the Japanese film industry responded with Godzilla—there were other responses too, of course, but Godzilla, to me, is the most telling. A subterranean monster, unstoppable, primordial, you can’t reason with him, you can’t bargain with him. But also he’s a guy in a rubber suit, and the civilization he’s crushing beneath his mighty feet is obviously miniature houses and toy cars. The humans have obviously been intercut from different locations, and aren’t in any danger at all. The movie wants us to stitch the horror together in our minds, to buy into it so it’ll work, but it’s also kept at a safe distance—how much can we feel through all that rubber?

Godzilla Minus One isn’t like that. A lot of the effects are still practical (the director, Takashi Yamazaki, got his start as a miniatures builder, and is a VFX supervisor as well as a director) but one of the extraordinary things about the movie is that it gives us real characters, who have all just suffered through World War II, who are having their lives destroyed all over again by this monster. It uses our expectations of campiness against us, and then startles us with intense emotion. I have now seen it twice in the theater, once in color and once in black-and-white, and both times everyone else in the theater was sobbing at the end. Here I think the trick is that it makes the mediation of tragedy so invisible you forget it’s there—but it also plays with the fact that we expect the rubber suit, or the CGI, and instead we get raw human suffering.

Of all the films I’m talking about I think Killers of the Flower Moon’s relationship to mediation is the most jarring.

The story of the Osage Nation’s sudden wealth and prominence is told through a series of silent film reels, as people model fancy clothes, pose beside cars, and pilot small airplanes. We are shown a glamorous world, a movie star world, and we are given only a few moments of vicarious thrill before we’re shown what’s being done to the people who live in those film reels. Like Asteroid City and Oppenheimer, the film creates a play between black-and-white and color stock—when the film drops us into the rich, dusty browns of Fairfax, Oklahoma, we are in a harrowing story of murder and betrayal, and all that glowing silver nitrate is a distant memory.

The next time we see film, in fact, it’s black-and-white news footage of the Tulsa Massacres. When an Osage woman screams “It’s just like Tulsa!” during an explosion, it’s a spike of revulsion as we watch white terrorists attack their Osage neighbors, just as they did Black Wall Street a few towns over.

And then there’s the film’s first ending.

I’ve written about it before, in our annual Things that Gave Us Nerdy Joy list, but obviously “joy” isn’t quite the right term here—it was more an overwhelming nausea, mixed with exhilaration that Scorsese had pulled it off. After this wrenching, brutal movie, a movie where I heard the audience around me holding its breath, gasping, groaning in disgust, we are suddenly bounced from an Oklahoma courthouse to an opulent theater.

The movie we’ve been watching, or at least parts of it, was a dramatization of the Osage murders, edited down and chopped up to fit into the Lucky Strike Radio Hour. We see a table of tools for the sound effects men, a full orchestra, and smartly dressed actors playing the people we’ve just watched for over two hours.

Do I have to tell you that they’re all white? That the one time we hear a Native character speak it’s a white man (Jack White, in fact) doing a racist caricature? We see the glittering audience lapping it up. We watch one of the actors fit some product placement for Lucky Strike cigarettes into a monologue. We see that the entire show is an ad, of sorts, for the nascent FBI, a victory lap for this new initiative that swooped in and saved the Osage… until it, too, betrayed them and denied them their money and land rights. We hear that all of the white murderers lived to ripe old ages. And when our greatest living filmmaker, Martin Scorsese, steps out himself to read Molly Kyle’s obituary, we learn that she died far too young, and that her obituary doesn’t even mention the horror she fought and survived. His reading is underscored by a syrupy violin solo, cueing all the nice white people in the audience to feel something.

With this ending, Scorsese does a very similar thing to what Wes Anderson did with Asteroid City. Unthinkable grief is refracted through so many lenses you can almost see it. Something that cannot be spoken is almost articulated. But the other thing is, and this is why he’s our Greatest Living Filmmaker, is that this isn’t the ending. We’ll talk about the real ending in a moment.

If you know anything about Christopher Nolan you know that he believes in the power of practical effects, and the power of those effects as transmitted through his bff, the IMAX camera. The point of Oppenheimer is to mediate the Trinity Test in a way, again, that no documentary footage can. The point is to put the audience there, to make us feel the impact, the beauty and terror of the bomb’s reality. (I’ve used that word, beauty, a few times now. I should probably put some thought into that. Is the mushroom cloud, billowing up into the sky, beautiful? I find it so. But how can I, when I know what it means?)

But it’s more even than that. I was nervous about this film. For all of my love of The Dark Knight and Dunkirk, I’m not actually a Nolan bro, and I was worried about making a biopic about Oppenheimer, about the depiction of violence, about the potential erasure of the victims of the bomb, of the possible valorization of the actions of the United States, without enough room afforded to the complexity of World War II. What this movie is, instead, is a subversion of a Great Man Biopic. It gives us the first hour of a great man biopic, as Oppy travels Europe and the U.S., has a Troubled Youth, finds mentors and inspiration, meets fellow scientists, and finally returns home to bring Quantumania to America. If this was a normal story he would probably find success teaching for a few years, possibly win a Nobel Prize, and almost certainly get fired for being Too Leftist.

Instead the film turns the Great Man Biopic inside out. There are arguably Great Men along the way, but Oppenheimer chooses to turn his talents to an act of supreme evil. He sells out his vague Leftist leanings in order to become part of a war machine. All of Oppenheimer’s wit, his verbal sparring, his performance of the role of Public Intellectual, his playboy shenanigans—none of it matters. At the dead center of the film is the result of all of his intellect, and it’s horror. Nothing but horror, and the reality we all have to live in radiating out from that black hole at the center.

As for mediation, the film shows us the characters mediating their own existence. It doesn’t show us Jean Tatlock’s death, it shows us Oppenheimer’s imaginings of it, both as a suicide and as an assassination. The slight-but-real possibility that the ignition of an atomic bomb will set the atmosphere alight becomes the subject of dark jokes and wagers. The bomb becomes a “gadget” because no wants to admit what they’re making. The movie doesn’t show us the agony the bomb causes—it shows us Oppenheimer’s face when he sees the agony, on a filmstrip.

Oppenheimer’s mediation of this story is essentially a dance, not between raindrops, but around its own horror. It only looks at it directly once.

A few days ago, while I was working on this essay, I took a break to walk to the bank. Because it (finally) snowed recently, a lot of the sidewalks are glazed over with ice, and since my legs don’t work too well I have to pick my way carefully through clear spots. At one point I had to stop dead because there in front of me was a woman aiming her phone at a building, surrounded by ice on all sides. After she walked on, I turned to see what she’d been filming—it was fallout shelter sign.

I re-watched A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood a few weeks ago. I’m not sure why. I tend to get a little low in January—lower than usual, I mean—and at some point in the middle of a day when I was supposed to be writing I randomly hit play on the Mister Rogers documentary, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? and it helped enough that I decided to roll with it and went straight into A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, which I remembered being pleasantly startled by when I saw it in the theater. I was startled again by just how much it commits to the bit of being a Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood episode.

And then, an hour and thirteen minutes into the movie, I found the key I’d been missing. A way to talk by not talking.

In Tom Junod’s profile, there a point where he talks about Mister Rogers’ love of silence, and how, when he received a Lifetime Achievement Emmy, he came out and said to the audience: “’All of us have special ones who have loved us into being. Would you just take, along with me, ten seconds to think of the people who have helped you become who you are…. Ten seconds of silence.’ And then he lifted his wrist, and looked at the audience, and looked at his watch, and said softly, ‘I’ll watch the time’…” and everyone in the audience had to do it, ’cause, come on, it’s Mister Rogers.

This scene is in Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, just as Junod describes it. A room full of stylish adults transformed into vulnerable children (one wonders if there were any Quakers in the audience who were able to relax for the first time all evening) as Mister Rogers asks them for ten seconds. You can feel the power of the moment, how it must have felt to be in that room—but also, ten seconds isn’t really that long, right?

But A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood takes that scene and transforms it into something else entirely.

One hour and thirteen minutes into the movie, Lloyd Vogel has had a breakdown, runs to Mister Rogers, hallucinates that he’s turned into a toy on the set of the Land of Make Believe, and collapses. After he wakes up, Mister Rogers takes him to a restaurant.

He asks Lloyd to join him in being silent. To “take a moment and think about all the people who loved us into being”—and Lloyd, being a Cynical New York Journalist, initially refuses. But then he does it. All the other customers in the restaurant quiet, and still. The movie is enveloped in silence. And, at one hour, thirteen minutes, and thirty-two seconds into the film, Mister Rogers flicks his eyes up, and meets the gaze of the camera.

He holds the camera’s eye, and ours, for 24 seconds. No soundtrack, no foley, no ambient noise. When I watched the film in the theater, the only sound was the rest of the audience breathing. We, in the audience or at home, were invited in to think about our own people who had loved us into being, and we were trapped in that moment, pinned by Tom-Hanks-as-Mister-Rogers’ eyes. (The entire moment of silence lasts 70 seconds, and, each time I’ve watched the film, I’ve felt every one.)

Watching it again a few weeks ago I recognized the emotion I felt, and I realized that this was the connection, the real connection, between these movies I can’t stop thinking about. It’s in the interplay between their meta elements, their nods to irony and pop culture knowledge, but also in the way they use silence like a sword to cut through all that irony.

Here’s a terrifying thought: most of the time I think humanity is better than it’s ever been. For all that people still fall in xenophobia and hatred and frothing hatred against the Alien and the Other, a lot fewer of them do now, I think. For all that people decry the loss of public civility, people are, often, being uncivil in the service of the vulnerable. Using any means necessary to get attention from the powerful, on behalf of the powerless. Civility is, after all, a thing we use to keep society running. If it’s breaking down shouldn’t we try to stop it, to revitalize it?

The side of me that’s a materialist sees us destroying each other and the only home that can sustain our life. A long slow suicide. The other side of me sees that we were given life and a home and have spent the entirety of our existence destroying each other and trashing the place—spitting in the Other Thing’s face, if such a Thing could have a face.

Both sides of me exist in a state of terror.

But back to silence.

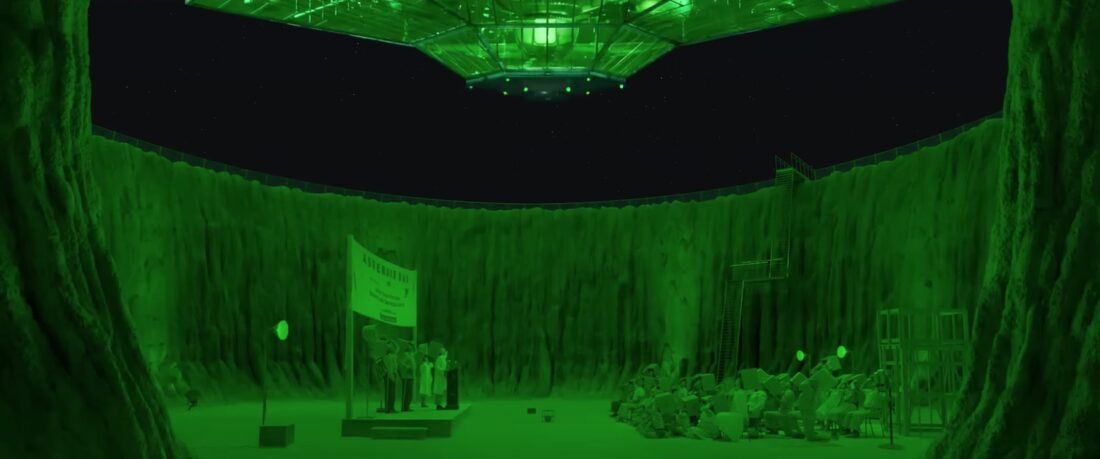

In Asteroid City the moment of silence is exactly where you’d expect it to be: the moment of contact with the Alien. As a glowing green ship descends over the Junior Stargazers and their families, the soundtrack fades out. The ship hangs in the air, the Alien comes down on a thin retractable rod, makes eye contact with the humans and poses for Steenbeck’s photo. He seems to understand that he’s being mediated, but he makes no effort to break the silence, no invitation to contact. He re-ascends with the asteroid, and as the ship sails away into the night, the soundtrack comes back in.

The moment of uncanniness is photographed, discussed from many angles, and even celebrated in song (“Dear Alien Who Art in Heaven”, this year’s second-worst Oscar snub) but the moment itself is shrouded in silence, and eludes capture.

Godzilla Minus One uses two scenes of silence to very different purposes. First, after a retro “Godzilla is attacking the city!”-type scene, Kōichi Shikishima, living in a state of shock and disgrace because he failed his kamikaze mission during the war, tries to save the woman he loves as the city falls around them. But when the monster uses his nuclear breath to lay waste to an entire neighborhood, silence falls as Noriko pushes him to safety, sacrificing her life for his. The soundtrack cuts out, leaving a ringing silence. We watch helplessly, as deafened by Godzilla’s roar as the surviving characters. The moment that is broken by the anguished wails of Shikishima.

The later moment mirrors the first. After all attempts to defeat Godzilla have failed, Shikishima seems to succumb to his fate, finally acting as the kamikaze his government meant him to be. He flies an experimental bomber straight into Godzilla’s screaming mouth. The movie itself holds its breath after the explosion; the silence is broken by a different kind of wail as one of his friends joyfully points to Shikishima’s parachute, carrying him to another chance at life.

Here the silence is used in a restorative way: when the sound drops away a second time we think it’s to lend weight to Shikishima’s death. Instead it becomes a moment when the movie honors his choice to live, despite his trauma. It’s the hope of a new life after the horror of war.

It shouldn’t be too surprising that Scorsese finds several uses for silence in Killers of the Flower Moon—each of the three of them took my breath away when I watched it the first time. The first scene, especially, is the heart of the film. It’s the purest moment of the relationship between Ernest and Mollie, if there are any pure, loving moments between Ernest and Mollie.

Mollie Kyle has decided to reciprocate Ernest Burkhart’s clumsy flirting. She buys him a giant cowboy hat, invites him in for dinner. They’re just starting in on a bottle of whiskey when a storm blows up.

She puts the glasses back down, tells him to keep the window open. Tells him “We need to be quiet for a while.”

He makes it about a quarter of a second before he blurts out: “It’s good for the crops, that’s for sure,” and she’s both exasperated and amused when she says, “Just be still.”

Older people used to do this where I grew up: you leave the windows open, the screen door open, you let the storm blow through the house, and you sure as shit don’t watch TV or sit on the computer. You honor the storm.

Mollie’s asking Ernest to be quiet with her. To allow nature to wash over him, to acknowledge his smallness, but his first thought, in that quiet, is of what he can take from nature. The storm isn’t a storm, a separate entity from him with its own designs, but a tool to make the crops better. But he clams up because she asks him to, he makes himself sit and listen to the rain and wind as it blows in through the window, erasing the illusion of separation between the people inside and nature outside. It is in this one moment, this image of silence that was used in all the press and became a bit of a joke in certain film bro corners, that any love that exists between them is born.

The other moment of silence, true silence, is in the long moment after Mollie Kyle confronts Ernest directly about the insulin shots he was giving her. Did he know what else was in them? He considers her. The soundtrack has dropped out, there is no birdsong, no breeze, no storm. Just, I suppose, if you turned the volume high enough to hear it, their breath. He insists it was only insulin, she stands, leaves the room, and lets the door slam behind her.

Only after he sits for a moment looking at the door does the soundtrack come back up—but it’s not the film’s soundtrack. No, this is when we cut to the horrifying radio program I mentioned above, a long, scalding mockery of everything that’s come before. Until we come to the film’s true ending.

In the end, we cut to the Osage again, dancing and singing in a mix of modern and traditional dress. We are Now, and these people, despite the best efforts of colonizers, thieves, and murderers, are still here. The camera zooms out and up, hovers over them, floats backwards away from them like the Angel of History that it is. And as their music fades what comes back in is silence, low rumbles of thunder, rain and wind in tall grass, birdsong, crickets.

Scorsese has transformed the theater, or your living room, into that room in Mollie Kyle’s house, windows open, storm blowing through. We’re being asked to be still.

Scorsese’s stillness is found in nature. It isn’t true silence, or absence (though I suppose you can find both of those in another movie of his)—it’s an attempt to still human sounds for those of the natural world. This might be armchair psychology on my part, but I think it’s because he’s a Manhattanite. A world stripped of traffic and sirens and construction probably feels exotic to him.

The other instance of silence I want to talk about, the one that drove me into writing this in the first place, is of course in Oppenheimer. I mentioned that A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood’s eye-contact lasts twenty-four seconds—Oppenheimer’s runs for twenty-five. How else can you mediate the Trinity Test, but through silence? Practically, it took a while for the sound and shockwaves to hit their observation point. But Nolan uses this moment for far more than that. He abandons us in the quiet, left to to contemplate the billowing blacks and golds of the first mushroom cloud. We, of course, know what happens next. If the cloud is beautiful to us, we also know what it means.

The silence is gradually undercut with the sounds of breathing, and broken by Oppenheimer’s memory of murmuring “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds” to Jean during sex.

It’s an extraordinary moment of interpretation, the bomb becoming a moment of destruction and creation at once in its creator’s mind. It’s the child produced by all of his intellectual birth pains, a creative act of annihilation.

Everything else in the movie revolves around this moment. Oppy’s panic attacks during clearance hearings and hollow victory speeches at Los Alamos echo with the rumblings of the bomb. The clockwork of a Great Man Biopic grinds away until it delivers us to the moment, and we already know that the H-Bomb and the betrayal of the clearance hearings are in his future. We already know how this story ends. This moment is the fixed point of the film, the empty sucking endless space, all that Great Man matter whirls around.

Was it relief that I felt? Or resignation? Why should this decision made by these short-sighted men be the absolute fulcrum of our world? What’s happened to me that I no longer demand a better future?

For all that I’ve been talking and talking and talking I find more weight in the silence. The way these artists have all had the same urge, to feint and flirt and dance to draw us in, only to take all of the fun away to make their point. This idea that we all, all of us, need to face up to what previous generations did and find a better way forward.

I don’t feel qualified to comment on the big things here.

Is it inhuman of me to write commentary on pop culture, to dig in and excavate the ways certain works of art engage with the things that really matter? Is it cheap? Cultural criticism is dying—or rather, it is being systematically destroyed by capitalist interests who have no originality of their own, and fear and resent anything they can’t monetize. Even thinking of my role as privileged or superfluous is an alarm bell—a society’s art is its core, its self-expression, its way of knowing itself. It shouldn’t be weird to want to engage with art, should it—don’t I have an obligation to make the most of it? So again, is it inhuman of me to try? Or would the inhumanity be ignoring all of this for easy funny posts about superheroes?

The actions of some people and some governments have made me feel sick to be a person. I don’t know what to do to help. I am in, and have been in, a state of despair. But, also, my despair doesn’t matter. It doesn’t help anyone, it doesn’t absolve me, and apart from all of that it’s a luxury our species doesn’t have time for.

And I have this space, right—this space where I can write into silence?